‘Cozycore’ and the comfort trap

Cozy gaming, cozy homes, cozy content, and the cozyweb – humans are retreating into a world of comfort and convenience, but at what cost?

In the introduction to Nightmare of Mollusc! I characterised the central theme – withdrawal – as a phenomenon that thrives at the crossroads of comfort and anxiety. In this post, I want to focus more on one of those elements, comfort, via the rise of ‘cozycore’ and the contemporary desire to turn off, tune out, drop out (of society).

For Nintendo, Animal Crossing: New Horizons couldn’t have launched at a better time. It was March 20, 2020 and much of the world had just gone into lockdown. Businesses shuttered. Schools closed. Millions were confined to their homes to reduce the spread of Covid-19. For many of the 13.4 million buyers of the game in its first six weeks of release, the subtitle – New Horizons – took on a very literal meaning. As their real horizons receded from view beyond their bedroom windows, a new, virtual world opened out before them: an island filled with friendly villagers, satisfying tasks, and a bustling ecosystem of fish, bugs, trees and flowers to grow and collect.

In a world defined by the slogan Stay Home, Save Lives, Animal Crossing was a much-needed source of comfort and escapism. The art style was cute and cartoonish, the gameplay simplistic and low-stakes – no combat, no grand quest, no timer ticking down. “You do what you want. You might renovate your home, buy a bunch of stuff you don’t really need,” wrote critic Darryn King a few weeks after launch. “Without doubt, part of the pleasure is precisely that sense of womblike coziness and security.”

In that time, the game also provided a sense of freedom (relative to the precarity and restrictions of the real world). Not only could players shape their avatar’s path through a real-time, multiplayer open world, but Animal Crossing acted as a platform for many of the activities that had been rendered impossible IRL. Out-of-work creatives organised gigs and fashion shows. Others earned real money through in-game services like photography, wedding planning, and interior design. Even more interesting were the ways Animal Crossing was misused as a simulacrum of open society. Hong Kong activists staged digital protests, after a crackdown on in-person demonstrations by Chinese authorities, and sex workers practised their craft on custom-made islands via an X-rated Internet of Things.

Still, it’s undeniable that the repetitive tasks and soothing aesthetic were a central factor in Animal Crossing’s success, especially at a time of unparalleled uncertainty and endless doom-laden headlines. (Numerous studies have tentatively linked video games – played in moderation – with positive effects on disorders like anxiety and depression. Games like SuperBetter channel “the psychology of game play” into direct, and successful, interventions.) For neurodivergent people and those with physical disabilities, it offered a hopeful vision for the long-term future of work, leisure, and human interaction, even after the pandemic had ended. As the disability advocate Suzanne Roman tells Reuters in a recent study on cozy gaming, the cozy gamespace can be revolutionary for people with autism, for example, as a place to socialise and make new relationships.

And for a minute there, it did seem like we were witnessing the birth of a revolution – the kind promised by Mark Zuckerberg’s Metaverse, or virtual worlds like Decentraland (launched in February 2020). Human reality seemed destined to split down the middle: a digital universe on the one hand, inhabited by cute and colourful avatars, and a world of flesh and blood on the other, like in Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash. Billions of dollars were bet on this brave new world. But in the end, it didn’t quite stick. The technology wasn’t quite there yet, or there just wasn’t enough energy to fuel its widespread adoption, after lockdown lifted and we all went back to work.

The fact is, during a plague, the optimal behaviour for large swathes of the population is a kind of withdrawal – watching Netflix, baking bread, going on solo walks, playing video games. Compare and contrast a familiar image of the apocalypse survivor that we’ve adopted from books, films, and TV. The Road, 28 Days Later, The Last of Us, Fallout, The Day of the Triffids:

Our hero is rugged, bruised and bloodstained, dressed in prepper-esque survival gear. Their movements are deliberate and decisive, designed to preserve precious calories – but when they do act, they act. They kick down doors, chop up the splintered wood, and make a fire with it. They hunt with rudimentary tools and skin the animals they catch, eat them off a spit. They travel by foot and fight when they have to.

In March 2020, we were offered a very different vision of the ‘apocalypse’ – and the hero didn’t look anything like a bloodied and bearded Viggo Mortensen, Cillian Murphy, or the Stalker in… Stalker. Enter a new archetype:

Our hero is bundled up in sweatpants, mid-skincare routine, Nintendo Switch in hand. Focused on themselves. There are no zombies to fight, no fellow survivors to dig out of the rubble, and nothing tangible to run away from. Instead they hide away, send emails, learn to paint, or to cook, and decorate the inside of their shell.

Games like Animal Crossing, Minecraft, and The Sims were “uniquely and uncannily suited” to the pandemic and its cast of quarantined characters, notes King. As the real world appeared to be falling apart, a retreat into the virtual became its own kind of virtue. People Clapped for Carers on their doorsteps, but the broader message said that everyone was a hero, so long as they stayed six feet apart. Looking back now, it seems obvious that the story couldn’t hold. As a consequence, it also seems clear that the metaverse was no more than a passing fad, a temporary coping mechanism – the game world was no match for base reality.

And yet… cozy gaming’s popularity continues to rise. According to online analytics, more people are talking about the genre than ever before; magazines offer seasonal round-ups of the coziest hits; Animal Crossing forums remain a hive of activity for virtual market traders and prospective new neighbours; and the r/CozyGamers subreddit boasts a quarter of a million members. The trend isn’t just confined to gaming, either. Cozy crime and romances have dominated TV and books for the last few years – branching out into other algorithmically-optimised genres like cozy kink – and Netflix has consciously dumbed down its content for even easier watching, attuned to viewers’ wandering attention and aversion to complexity. Meanwhile, fashion has continued to fetishize lavish comforts (Billie Eilish on the red carpet in a Gucci duvet, Tommy Cash wearing a full bed at Paris Fashion Week, pillows and plush padding on every other catwalk).

Online, the outsized presence of cozy culture is even more obvious. On Instagram, tens of millions of posts are labelled #cozy, #cozycore or some other #cozy-related tag. #cozyvibes. #cozystreetwear. #cozyhome. #cozybedroom. Every year, more and more users seem to rejoice as the nights draw in and #cozyseason begins, sharing the related food, drink, and interior decoration trends. (Of course, you don’t need a galaxy projector, blanket hoodie, or melatonin gummy to feel cozy, but it’s unsurprising that cozycore has converged – like any trend that propagates online – on a kind of excessive consumerism. On the internet, all roads lead to a product available for purchase on amazon.com, or some similarly abstract online storefront.) TikTok users are similarly captured by Big Hygge, with more than 1.5 million posts labelled #cozy, plus various offshoots. #cozystyle, #cozygirl, or #cozysetup, where users share their favourite configs for sending emails and media streaming, complete with candles and pastel-hued backlighting.

As Kyle Chayka spells out in a recent New Yorker article, cozy media spilled out of our screens and into our homes sometime during the pandemic, transforming the look and feel of our physical surroundings, from tech, to soft furnishings, to the clothes we wear. Today’s cozy gamer isn’t just immersed in the virtual universe on their Switch; they’re “completely ensconced in a serene environment, a self-contained digital and physical cocoon”. This is ‘cozycore’ – a lifestyle, a whole way of being, modelled on an archetypal hero of social distancing, the 24/7 lo-fi hip hop girl.

If comfort means existing in a state of physical and mental ease, cozycore is comfort taken to its extreme. The terms are almost interchangeable, but slightly different in some meaningful ways:

Getting comfortable is about learning how to move smoothly through the world; cozycore is about reshaping the world with your comfort and convenience in mind.

Comfort depends on how a person relates to their environment; cozycore believes in a world with you at its centre – an unchanging, immovable object.

Comfort can look like many different things to many different people; cozycore is an aesthetic, as well as a state of mind or way of being.

And although for most people the plague fears have faded (for now…), we embrace this way of living more than ever: we stay home and cloister ourselves in a soft, smooth world with no sharp edges.

Data from the last few years matches up with a prevailing sense of this post-pandemic vibe shift. Young people spend much more time alone than they did a decade ago, and time spent in-person with friends has reduced by nearly 70% since 2003. An uptick in working from home has helped facilitate our withdrawal from public life, but leisure time follows a similar trend: a growing majority of restaurant traffic comes from “off-premises customers”, while entertainment continues to shift away from public environments and into the home. Online grocery shopping spiked during the pandemic, but it’s remained popular ever since – and even in a real supermarket, most human interaction has been replaced by characterless, agreeable machines. Relatedly, Gen Z reports higher levels of loneliness than any other generation.

Meanwhile, social media offers a lacklustre proxy for IRL social spaces like cafés, clubs, shops, and bars, which are disappearing rapidly in a vicious cycle of cause and effect. No doubt this has some physical repercussions – less sunlight; more time sitting down, staring at a screen – but moving online facilitates our retreat into a world of mental and emotional comforts, too.

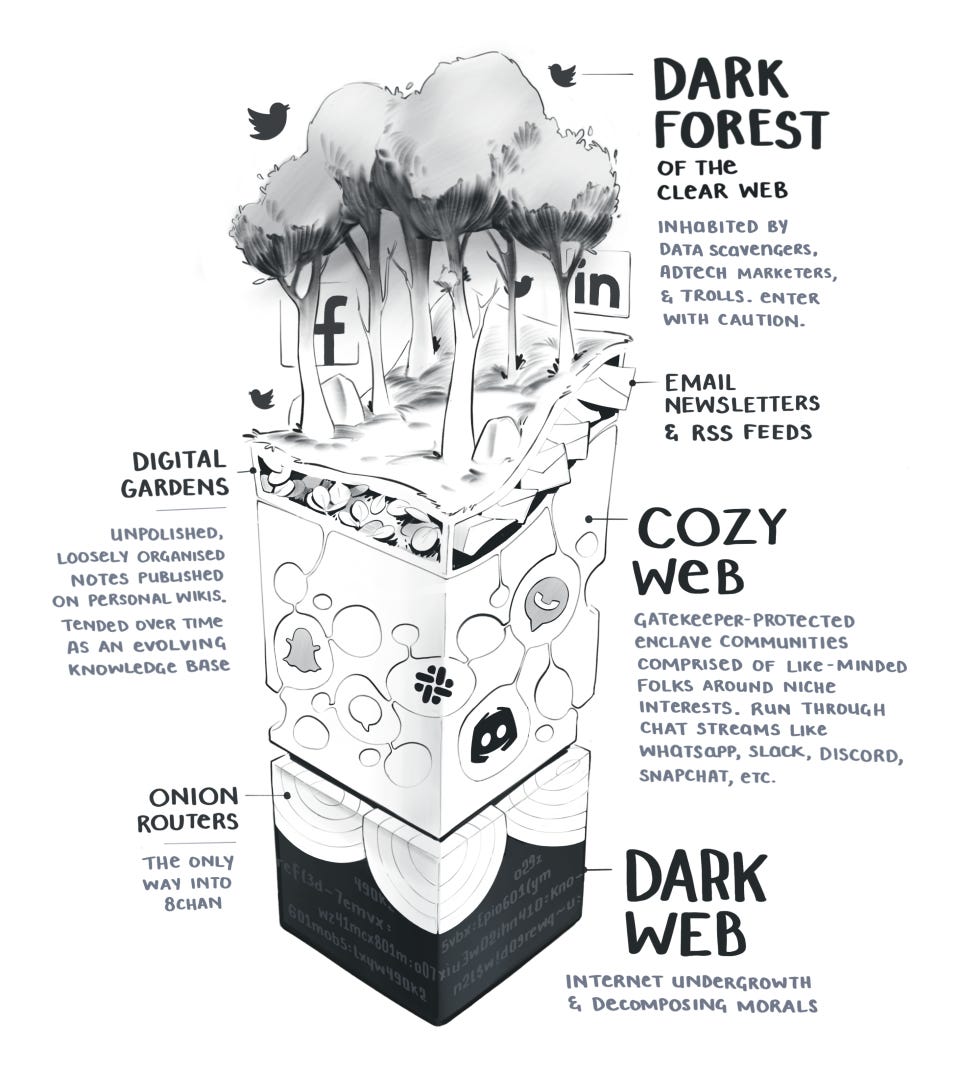

The term cozynet was coined by Venkatesh Rao back in 2019 (see also: Maggie Appleton’s very helpful illustration). It describes an online ecosystem formed of invite-only group chats, password-protected Discord channels, and subscriber-only newsletters: “Gatekeeper-protected enclave communities comprised of like-minded folks around niche interests.” On the one hand, the cozynet represents a kind of oasis for internet users, away from the trolls, data harvesting, predatory advertisers, censorship, and hate on mainstream social media. On the other, its philosophy might be seen as fundamentally isolationist. In a cybernetic cycle of mutual reinforcement, there’s a temptation to withdraw ever further into (and hold ever tighter) our niche interests and esoteric beliefs. Worst case? The cozynet just accelerates the fragmentation of an already atomised culture.

Of course, the big social platforms aren’t much better. Far from “bringing the world closer together” (which would mean bringing us into contact with ideas we might disagree with) they typically sort us into sub-communities of people just like ourselves. If we weren't already used to it, the effect might seem eerie, like encountering your doppelgänger, but it’s easy to get comfortable in the frictionless arena of shared references and political consensus. And as platforms splinter further along ideological lines – like left-wing users leaving X for Bluesky en masse – we risk breaking into even smaller groups.

Maybe I should clarify: I love to be cozy. I like how it feels, and I’m well aware of the proven positive effects. Light, scent, colour, and texture have a significant impact on our mood and mental health. So do ‘mindful’ activities like colouring books or rewatching a favourite TV show, especially in times of uncertainty or cognitive stress. And I don’t want every moment of my online life to be adversarial. A bit of comfort is no bad thing.

But comfort is also a trap. The way a muscle might atrophy if you don’t use it enough, so does our attention, our critical instincts, and our willpower (according to some influential social psychologists). The further we retreat into our shells, the more the spiral tightens, and the more energy it takes to get out again.

This is particularly problematic in a world where everything is increasingly tailored to our comfort and convenience – real or virtual, mental or physical. For the more privileged people in the world (probably everyone reading this) there’s more comfort, more convenient products, more dopamine and distraction available than we know what to do with, more than we could consume in a single lifetime. And it seems inevitable that there’s even more to come, thanks to growing automation, cheap and accessible luxuries, and intelligent machines designed to do our difficult thinking for us. If we want to experience struggle or deprivation, most of us have to actively seek it out. But this doesn’t come naturally.

Technology has already changed the world at a blistering pace, and it’s only accelerating; meanwhile, we’re still stuck in brains and bodies evolved for the lives of our ancient ancestors (in terms of speed, biological evolution is no match for human culture, science, and industry). To serve our basic function – to pass on our genes and maximise their chance of their survival – humans are essentially programmed to pursue pleasure, avoid pain, and conserve energy, to reach a stable state, and take the path of least resistance to get there. This was very useful for our ancient ancestors; it would be very useful if we were thrust into a post-societal wasteland. It’s less useful in a functioning, 21st-century civilization, where pleasure is abundant, pain is easily avoidable (in the short term), and it takes very little energy to get anything done.

Humanity has reshaped the world to be frictionless, cozy; and in doing so it’s also changed itself. We no longer have to undergo the task of sourcing our own food, building shelter, or even forming real and complex relationships – that’s what the virtual, anthropomorphic villagers are for. In the short term, the replacements for these tasks feel good; they trigger all the right responses. The side effects come later: stasis, atomisation, and fragility (I can’t imagine managing any long journey without Google Maps, even though I know people used to all the time). One day you wake up, and realise you’ve withdrawn so far around the shell’s ever-tempting spiral corridor that you can’t see the sunlight any more.

When I started Nightmare of Mollusc!, I decided that I didn’t just want to be critical. I’d be a hypocrite to write about comfort and withdrawal – the retreat of humanity into its own shell – and not take the risk of trying to share some more productive ideas or answers to the questions I’ve raised. So, aware that I might sound dumb or presumptuous in retrospect…

The opposite of comfort is challenge. And maybe the way to break free from cozycore’s worst incentives, and escape the comfort trap, is to reintroduce a sense of this challenge into our lives.

A pre-presidential Teddy Roosevelt preached a version of this in his 1899 speech The Strenuous Life, contrasting “a life of ignoble ease, a life of that peace which springs merely from lack either of desire or of power to strive after great things” with “the doctrine of the strenuous life, the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife”. Instead of “busying ourselves only with the wants of our bodies for the day”, he argues, we should foster a sense of adventure, risk, effort, and responsibility; a deeper happiness lies beyond a life of “mere enjoyment”.

Nietzsche (🚩) draws a similar picture via his antithesis to the Übermensch in Thus Spake Zarathustra – the ‘Last Man’, a symbol of passive modernity:

“One no longer becometh poor or rich; both are too burdensome. Who still wanteth to rule? Who still wanteth to obey? Both are too burdensome.

[…]

They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health.

‘We have discovered happiness,’ – say the last men, and blink thereby.”

Needless to say, the dichotomy drawn by Nietzsche here has been twisted to some indescribably dark ends. Scroll a couple of paragraphs through Roosevelt’s speech, and you’ll also see how ideas about a ‘superior’ way of life, when extended to the level of the nation, were used to romanticise past wars (admittedly, this includes the Civil War and the freeing of slaves) and justify future bloodshed by “stern men with empires in their brains”. Similar conversations about masculinity and the ‘noble’ cause underpin arguments for violence and conflict today, made by Boogaloo Boys and Dark Enlightenment figures with an increasing stranglehold on US politics.

But to be clear, embracing challenge doesn’t require going to war, on the personal or the national level. I’m also not advocating a return to the Good Old Days, when men were men, ate a diet of raw meat, and took their baths in ice water – a fantasy world often evoked by right-wing tech bros and ‘off-grid’ survivalists whose subsistence depends, ironically, on their social media metrics. (Although if that works for you, great; just be careful of food poisoning!) Too much challenge, like too much comfort, can become a very bad thing over time. Somewhere in the middle of the two, though, there’s a sweet spot.

Rayne Fisher-Quann makes a brilliant comparison between walking and writing (vs typing a prompt into an AI tool) in a recent Substack essay, Choosing to walk, which gets to the heart of what it means to embrace challenge as an individual. She writes:

“I think of writing a lot like walking. It’s rarely the most popular, the most effective, or the most efficient way of getting to your destination. I don’t always want to do it, and it’s not always technically enjoyable; sometimes it’s boring or slow, sometimes it’s tiring and pointless, sometimes it’s cold or wet or windy and I’m retracing the same steps around my neighbourhood that I’ve walked a thousand times and it sucks and I’m miserable and wish I’d stayed inside. Nonetheless, I always feel worse in my body and mind when I avoid it for too long...”

“When you choose to walk, you choose not to pursue immediate gratification or even comfort but simply to expand the number of things that might happen to you. Walking invests in the potentiality of your experience with almost no promise of tangible reward at all, which is something like being alive.”

Challenge doesn’t even need to have a strict purpose or direction (although it might feel even better when it does). It could mean walking up the hill instead of taking the bus. Taking the stairs, not the escalator. Watching Fire Walk With Me or an Adam Curtis documentary, instead of three or four episodes of Emily in Paris. Choosing not to eat so much sugar. Spending thirty minutes on a sketch, instead of thirty seconds with DALL-E 3. Reading something that you know you might disagree with. Consciously thinking about difficult topics. Writing about them, publicly. Going outside, in the cold, and tending a literal garden instead of terraforming your way to a lesser satisfaction on your island in Animal Crossing.

Cozycore feeds on our aversion to risk and difficulty, and a preoccupation with the shape and feel of our own lives; the choices described above are fed by a sense of adventure, curiosity about what lies outside our comfort zones, and optimism about what the future can look like (and feed these things in turn). They aren’t easy choices to make – that’s kind of the point – but they get easier to make the more they’re made, like the muscle that learns to lift a bit more weight over time.